Review by Maria Teresa De Donato

“On September 1, 2008, I resolutely resigned from Xihai Metropolis Daily and embarked on a trip I had been planning: starting from Qinghai to Tibet in the South and Xinjian in the North, the two most magical places in China. To my mind, the Xinjiang desert in the north of Kunlun Mountain and the Tibetan Plateau in the south of Kunlun Mountain are the Yin-Yang center of the Eurasia continent. … It seems to me that all mountains start here, and all mountains end here.” (Cao Shui, 2010, 2018, p. 94)

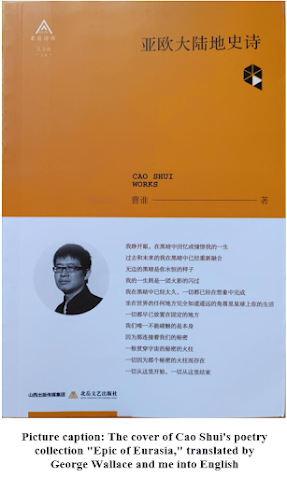

The above statement of Cao Shui, a famous Chinese Author, Poet, and Screenwriter, paves the way to a better and more comprehensive understanding of the spirit, intentions, and content of his publication Epic of Eurasia.

We already met Cao through his work Flowers of Empire, a poetry collection in three languages translated and published by Fiori D’Asia Publisher, that I had the pleasure and honor to read and review. As I explained in that occasion, “reading, interpreting, and reviewing Flowers of the Empire by Cao Shui was not easy but extraordinarily fascinating and equally exciting” and that “A great culture, a profound sensitivity, and an equal capacity for analysis and to see the World at 360º emerge in this literary work as the flagships of Cao Shui’s poetics.” (De Donato, 2023)

As we are about to see, Epic of Eurasia is characterized by some elements that play a fundamental role in developing its narrative.

First of all, the real protagonist of this work is the Eurasia continent, “once the free dreamland of mankind” (p. 14), located in Mesopotamia. According to history, human civilization started in this area. Furthermore, there is a frequent reference to both the Tower of Babel and the Pamir Plateau, with the latter being a mountain range located between Central Asia and Pakistan, at the junction with the Tian Shan, Karakoram, Kunlun, Hindu Kush, and the Himalaya.

Cao Shui – consciously or unconsciously – seems to use the reference to Pamir Mountain as a metaphor or even as a foreshadowing of the upcoming realization of the new Tower of Babel, whose reconstruction, at least in an emblematic and cultural sense, is the ultimate goal of his very literary production.

As Cao explains in this work, “An epic is a sign of the collective spirit of a nation. Today, the existence of the epic has long disappeared. We are facing a world rather than a nation. We live with science rather than divine stories. We employ free verse rather than metrical poetry.

Consequently, the idea of a modern epic is confronted by an unprecedented crisis of legitimacy. The epic was originally the original literary form. Inside, it included a story describing the occurrence of a whole nation…” (p. 13) “Today, we have no divine story and have lost a sense of indigenous rhythms. However, because of this, poetry seems to have returned to itself for legitimacy. … what we are facing today is not individual nationhood but planet citizenship. And in that light, our world needs to create or restore a kind of ‘Great Epic’ for our time.” (p. 14)

In Epic of Eurasia, therefore, Cao feels the need to recover what has been lost. His Epic is a combination of ancient and modern references, myths, stories, symbolisms, truths, dreams, and fantasies spanning from the South to the North, from the East to the West, and from Earth to Heaven; its goal is “to build or declare a symbolic system with shared images or elements or ‘objective correlations’ to communicate our spirit and the essence of the world.” (14)

Following the birth of languages that occurred after the construction of the Tower of Babel, people scattered eastward and westward. They started talking in different languages, using different symbols and totems, yet there were always similarities or common aspects preserved in every culture and civilization. Hence, the latter would indicate a common ground, common roots, and a universal spirit that never disappeared despite the passing of time, even millennia.

Although part of ancient history that was passed onto us is now interpreted as a ‘myth’, some questions arise:

- Why did our ancestors, for millennia, firmly see them as truths while, on the contrary, many people nowadays doubt their veracity and prefer seeing them as myths when not even as fairy tales?

- Although history has been characterized by one civilization overpowering another, by one war and conquest after the other, and by the tragic loss of millions of lives, shouldn’t we sit and ponder on the fact that we might have, indeed, one and an only origin, thus proving that we are, in fact, all brothers and sisters after all?

The descriptions of historical events and parallel narratives of different civilizations encourage the readers to find the proper answers to these questions of the utmost importance.

A second important aspect that is regularly mentioned in this publication relates not only to Yin and Yang but also to the symbols of Fire, which may represent both destruction and creation or even purification, Water, Earth, and Heaven which are paramount in the Chinese culture. They all have a plurality of applications and meanings – from literary to symbolic, from metaphorical to transcendental.

Mankind’s cruelty is highlighted in this work, whose verses point at Man’s dominance over Nature and wildlife, having no consideration or respect whatsoever for the Sacredness of Life:

The killer looks for a target in the crowd, like a normal person

…

Those who do evil enjoy glory

Those who do good die in poverty (p. 49)

which stresses the aberration and paradox of circumstances Mankind has been accustomed to:

A wolf walks towards Aries

A butcher walks towards the horse

The wicked walk towards the good

We walk forward into the darkness (p. 49)

Evil reigns, therefore, abundantly on Earth, while Mankind keeps moving blindly in the darkness.

A sense of profound loneliness is always present and emphasized in Cao Shui’s verses. It’s not only a matter of physical distance from others but, above all, of spiritual one. It is ‘le mal de vivre’ (the pain of living), the full awareness that, although we are all in the same boat, so to speak, each one of us stays so individually, locked in his own suffering:

No matter where I go, I’m alone

Everyone is far away

The vortex is always empty (p. 49)

I can’t leave the vortex

…

…

I am always in the most empty places

This lonely world!

All around are idle people (p. 49)

The center is always empty

I can’t get rid of the emptiness in my life (p. 50)

According to Cao, other crucial themes are Knowledge and Awareness: they are both paramount in Life. According to the Author, we shouldn’t, however, depend on others to gain them. We may inspire people and empathize with their sense of bewilderment and hunger for Knowledge and Awareness, but ultimately, it’s up to each of us to find our own way to reach that goal.

One of the main tasks of a Poet is to bring all of this to light. However, so long as the Collective Consciousness is not ready to become fully aware of the intrinsic and most profound meaning of a Poet’s message, people will keep walking in the “fog” and hear his “distant echo” (p. 54)

A deep feeling of not belonging and of Life’s nonsense is also present in his verses:

My head is half inside and half outside

My body is half in the earth and half in the sky

People I know are waiting for me. I’ve been gone forever

What’s the difference

…

…

Those who go will come, those who come will go

What’s the difference (p. 51)

Throughout his work are evident Cao’s desire to pave the way for a better understanding of the dynamics that regulate our World and make Mankind and all Creation suffer and his attempt to help people comprehend and visualize the possibility of something new that might unify in a spirit of brotherhood, peace and love all Humanity.

Following Cao’s writing from start to end is not, indeed, an easy task. His writing requires undivided attention and focus not to get lost in the many accounts, details, metaphors, and historical and geographical references he uses.

The latter span from one culture to the other throughout the millennia, although the epicenter remains the Eurasia continent, and embraces all kinds of civilizations and beliefs with special regard to the ancient world powers that followed one another in Mankind’s history.

Reading his works can be quite challenging at a time, yet absolutely exciting, fascinating, and even more so rewarding for those who love to dig into multiculturalism and are passionate about ancient history. The eclectic, more versatile personalities will find ‘bread for their teeth,’ so to speak. On the contrary, those who might have a more linear way of thinking, though still interested in reading and appreciating Cao’s work, might need more time and patience to stay on track for reading and fully enjoying it. There is nothing wrong with being ‘eclectic’ or rather ‘linear’ when it comes to personality traits and ways of thinking. It’s only a matter of how our brain works, and there is nothing we can do about it. It’s in our DNA.

Hence, no matter if we like Cao Shui’s literary production or not, we cannot but acknowledge that he is one Man and one Author of a kind, a Writer, Poet, and Screenwriter of great cultural and human depth.

We wish with all our hearts that he might reach his goal of creating the New Babel Tower, at least culturally.